Image via Wikipedia

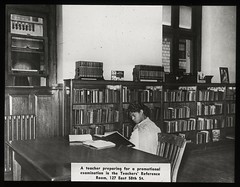

Image via Wikipedia

Today I dedicated the first lecture of my African American Rhetoric class to my colleague Robert Branham, the one who wrote the Malcom X article as well as the editor of the leading reader on African American rhetoric. When he died, of prostate cancer, younger than me, smarter than me, funnier than me, I thanked him for being my friend since we were college debate opponents.

I had done some African American projects with him, and I promised that I would not let my discovery of the African American voice in public messages (but especially in debate) be neglected, but promised (along with Bill Newman of Emory) to continue this search and discovery. This is my own limited contribution to the effort, but I will try to do better as the semester goes along and beyond.

This one is for you, Bob. And for you, Neil.

Here is my lecture for today, given to my students:

INTRODUCTION TO AFRICAN AMERICAN RHETORICAL THEORY

Investigating concepts from Karenga, Alkebulan and Garner

Western rhetoric has been recently dominated by:

Consumerist approach to rhetoric pressed into the service of vulgar persuasion, advertisement, seduction and sales.

It has abandoned the classical Aristotelian rhetoric of deliberation and action in the interest of the polis, but has also ignored and denied contributions from other cultural traditions.

In this African conception of rhetoric it is a practice of communal deliberation, discourse and action oriented towards what is good for the community and for the world. This essence of community is both expressed in the goal of the rhetoric but also in the practice of the rhetoric. It is designed to help bring good into the world.

The Odu Ifa of Yoruba land claims: “Humans are divinely chosen to bring good into the world,” that is their mission and communication is the way that they do that. They are uniquely situated among living creatures to do this.

This is not to replace but to contrast and add to classical European and Greek approaches to rhetoric. Often this enterprise uses Kawaida philosophy, the consolidation of enduring African theory and practice in rhetoric.

Kawaida invites us to ask what Africa has to offer to the understanding of human communication in the interest of benefiting all humanity. We should engage in ancient and modern traditions, written and practiced, oral and other forms. It has traditionally been concerned with building community, affirming human dignity and enhancing the life of the people. More recently, it has been a rhetoric that concerns itself with struggles for liberation in the political, economic and cultural senses as well as a rhetoric of resistance.

It is not just about “tradition” in the way we usually mean it, but also in terms of Location, the continual reference to context and centeredness. It is about history as well as tradition.

It emphasizes communal discourse, deliberation and action. It is a rhetoric of resistance, formed in the crucible of struggle. It is not just about African people, but also about all of humanity. It is the rhetoric of reaffirmation, for African peoples as well as all of those who are not considered fully human. It is also a rhetoric of possibility, about what we can do that is new as well as what is traditional.

NOMMO

The historical cultural triumphs of ancient Egypt (Kemet) stands as one of the main modal periods for Africa. It was the first and one of the most developed societies in the world. It has been clouded over by European jealousy and attempts at outright theft.

• It was African, not European.

• It was not a huge slave society, free people who volunteered their work built the pyramids. Europeans needed it to be “slave” because of what they had done with slavery.

• It was the basis for much of so-called “western” civilization. The great works of law, medicine, and rhetoric began there, not in Greece thousands of years later. Hippocrates admits in his text that he is a servant to the great Kemetic healer Imhotep.

While the historic tragedy that was slavery and its results tried to erase these traditions, it could not be erased. African rhetorical traditions reappeared during the resistance of the 19th and 20th centuries, and especially in the rhetoric of the 1960’s, both “civil disobedience” and “by any means necessary.”

Nommo is the creative power of the word. While conceptually rooted in the rhetorical teachings of classical Kemet, the word itself comes from the traditions of the Dogon people of central Africa. The creator spirit sends Nommo to the world in the form of speech to assist humans in the forWard movement of history and the reorganization of the world. It is through the word that weaving, forging, cultivating, building family and community and making the world better, bringing good into the world. Nommo is the unity of water, earth and fire, and the unity between male and female.

It was not until the 20th century that western rhetorical theory began to fully understand the generative power of symbols, that they create a reality, that they shape our experience, as opposed to the more traditional view that they are just tools that we use to “get our way.” The rhetorical basis of Nommo puts African rhetorical theory ahead of Greece, Rome and Renaissance Europe in this way.

As Karenga puts it (p.8):

It is this sacred, indispensible, and creative character of the word, as an inherent and instrumental power to call into being, to mold, to bear infinite meanings, and to forge a world we all want and deserve to live in, that seizes the hearts and minds of the African American creative community and becomes a fundamental framework for developing, doing, and understanding rhetorical practice – both its oral and literary forms.

ASANTE

African American rhetorical scholar Molefi Kete Asante is largely responsible for this rebirth of traditional African rhetorical theories. His major early themes included:

• Africans brought a sophisticated oral style to the western hemisphere

• Africans brought with them a different rhetoric, not just a concern with influence and ends

• African American rhetorical tradition retained and further developed the concept of nommo, African Americans understand the transforming power of vocal expression.

• Because African Americans were denied reading and writing they learned to rely on the spoken word.

• The enslavement experience stands astride all discourse like colossus, whereas the discourse might be about discrimination or voting rights, but the slave experience is at its basis.

ANCIENT KEMETIC (EGYPT)

Kemetic rhetorical studies pre-date similar Greek activities. The Book of Ptahhotep offers guidelines and principles for good speech. For Kemetics, eloquence and good speech is a unity not just of techniques that are successful but also that lead to what is good for the community. The three standard Greek modes (logos, ethos, pathos) are brought together, so that if techniques are successful but lead to bad for the community, then it is not real eloquence.

Speech is conceived as an ethical activity, because it is a tremendous power that can be used for good or evil. For them, a “good” speech is not just effective, but is also ethically and morally good.

Maat is the Kemetic standard for what is “morally good.” In application to speech, Maat means that it is truthful speech. Truthful speech creates its own ethos and is in and of itself persuasive. This stands in contract to the artifice and dissimulation that is so important in modern western rhetoric that has been put to the service of seduction and sales.

The Book of Ptahhotep is also the major source for the understanding of Maat as an overall moral concept. The central focus of the book is a narrative about the calls petitions for justice from a normal peasant named Khaunanup. He makes a number of appeals to figures in power and these demonstrate the speech that is both “moral” and “effective.” The point here is that rhetorical eloquence is not necessarily that used by leaders and important people, but by all people – peasants, servants (and men and women) can be rhetorically eloquent, and are expected to be so. It is no surprise that the model orator in this Kemetic text is a farmer.

Humanity is seen as a spiritual force. In African rhetoric and African American rhetoric there is no line of demarcation between the spiritual and the secular. The speaker calls all of us to go to a higher place and improve ourselves not just as physical but as spiritual beings. Communication is the way that moral and spiritual ideas are transmitted.

If the greatest spiritual law is the law of love, then great communication events are examples of this. Asante has said that there are no speeches by hatemongers that have gone down in history as great speeches. There will never be any, because the overwhelming judgment of history is a moral one and the speaker who imperils the forward march of human dignity will not live in the minds of the future. It is the champion of righteousness who is the true victor in rhetorical traditions.

The African culture tends to be a very oral one, and thus rhetoric is paramount in its importance for the human spirit, for the benefit of human conditions and in the achievement of personal and social harmony.

African and African American rhetoric does not compartmentalize rhetoric, poetry, literature, prose and drama. All these forms are interwoven into a discourse designed to achieve important goals and ends.

ARISTOTLE RECONSIDERED

Aristotle might be a bit unfamiliar with modern rhetoric. He was clear that rhetoric had to have an ethical dimension, that truthful arguments were always stronger, and that rhetoric needs to serve the ethical dimensions of politics.

Today we see the dominance of technique in discourse, of the use of rhetoric to control, manipulate in a way that can be mapped out in advance. The fault may not lie with the extended vision of Aristotle, but with the basic definition of rhetoric, “the faculty for observing in any given case the available means of persuasion.” This focus on persuasion through any available means has become the central tenet of current rhetorical practice.

Kemetic texts called “sebyt” are instruction manuals for how officials and others in important positions should conduct themselves, but it also contains advice on how communication should take place in family life and community life. The Kemetics viewed the unity of private and public lifer as important.

Fox has identified five important canons of ancient Kemetic rhetoric:

• Silence (self control)

• Good timing

• Restraint

• Fluency

• Truthfulness

The sebyt of Ptahhotep is the oldest complete text in the world. It is a set of instructions to his son about how to engage in public service.

Karenga indicates four ethical concerns of classical African rhetoric:

ONE: DIGNITY AND RIGHTS OF THE HUMAN PERSON

The ethical concern for the dignity of every human person is a fundamental aspect of rhetorical practice.

Be not arrogant because of your knowledge. Rather converse with the unlearned as well as the wise. For the limit of an art has not been reached and no artist has acquired full mastery of an art. Good speech is more hidden then emeralds and yet it is found among the women who gather at the grindstone.

In an example, Pharaoh is cautioned not to use people as experiments or for unnecessary reasons, in this case with a convicted prisoner. Each person is part of the “flock of God” and must be respected.

The petitions presented by Khunanup are all for common people, who should be respected just as much as the most famous. His appeals for justice are based on Maat, the equal dignity and rights that all should have. Maat needs to be in its rightful place, as a foundation for political, judicial and social practice.

Leadership is seshemet, as in “working out” or “proving” a problem in mathematics. This must be done through consultation and communication. The speaker is called on to not just speak to but also to speak with those concerned so that a proper conclusion can be reached. Thus, Kemetic rhetoric tends to be consultation as opposed to unidirectional.

TWO: WELL BEING AND FLOURISHING OF THE COMMUNITY

In the text Count Harkhuf explains why he feels he is worthy of respect. He locates himself in his community and his family, and then speaks about the way he did good for the people, especially the vulnerable. “I gave bread to the hungry, clothing to the naked and brought the boatless to land.”

Iti, the treasurer, says, “I am a worthy citizen who acts with his arm. I am a great pillar of the Theban district, a man of standing in the Southland.”

Lady Tahabet defines herself as not just a worthy daughter, but as a worthy citizen, when she says, “I was just and did not show partiality. I gave bread to the hungry, water to the thirsty and clothes to the naked. I was open-handed to everyone. I was honored by my father, praised by my mother, kind to my brothers and sisters and one who is united in heart with the people of her city.”

This is different from many of our western conceptions. In the west, “I think, therefore I am.” In a Kemetic sense, “I am related and relate to others, therefore I am.” I discover myself through being with, being of and being for others. Others listening are not merely audience, but co-agents and co-participants in creating and sustaining the just society and the good world.

THREE: THE INTEGRITY AND VALUE OF THE ENVIRONMENT

Moral obligation is related to all parts of life. As one has obligations to other people, one also has obligations to all of life – to nature. Maat requires worthiness before the Creator, nature and the people. If there is damage and degradation, there is an obligation to restore and repair. This obligation implies:

• To raise up and rebuild that which is in ruins

• To repair that which is damaged

• Te rejoin that which is severed

• To replenish that which is lacking

• To strengthen that which is weakened

• To set right that which is wrong

• To make flourish that which is insecure and underdeveloped

FOUR: RECIPROCAL SOLIDARITY AND COOPERATION OF HUMANITY

We have obligations to each other and we must cooperate through our communication. This is in conflict with the artificial eloquence, deceptive discourse and instrumental reasoning that may serve some but not all of humanity. Likewise, this questions the nature of the closed public square, saying that human communicative exchange should include all of humanity.

The Book of Ptathhotep, there are examples:

“He who does justice for all the people, he is truly the prime minister.”

Leaders and speakers must stand for and speak for all marginalized and oppressed people as well as those in the mainstream who are privileged.

Doing good leads to solidarity. “A good deed is remembered,” and also, “do to the doer that he may also do.” When Maat is a part of rhetoric, it leads to two kinds of solidarity:

• Solidarity of action

• Solidarity of understanding

These are both achieved through communication.

Lady Ta-Aset says: “Doing good is not difficult; just speaking good is a monument for one who does it. For those who do good for others are actually doing it for themselves.”

In the Dogon text, it is written that, “Doing good worldwide is the best example of character.”

AESTHETICS

For African people, language is art. Art is not for the purpose of artistic expression and creativity, but is always functional. In the west we separate art from life, but this is not the African conception. It is not the product of the artistic activity, but the process that is important. That process is always a part of living.

Art has the same ethical obligations as rhetoric. Rhetoric is an art.

Call and response is one example of aesthetics in rhetoric. One does not just listen to, but responds to and participates in discourse. The discourse is a living presence and the audience responds and becomes a part of it.

In African rhetorical tradition and specifically in African American rhetoric the audience engages in this way. In church, in meetings, in political speeches. The rhetorical event becomes a communal one.

Aristotle posed the concept of the enthymeme, an incomplete argument completed by the audience. This is effective because it allows audience participation that increased acceptance. The entirety of African American rhetoric already knows this. Knowles-Borishade puts it this way:

Responders (audience) are the community who come to participate in the speech event. They are secondary creators in the event, containing among them a vital part of the message. It is they who either sanction of reject the message – the word – based on the perceived morality and vision of the Caller (rhetor) and the relevance of the message. The notion of community or group sanction is the basis of the African call and response tradition.

We will examine many other aesthetic elements of African American rhetoric in the weeks to come.

STRIPPED OF AFRICANNESS

What signals a real African presence in a discourse? Some might be African American in appearance but not in substance. Danny Glover in Switchback or Morgan freeman in Shawshank Redemption. They are African American when they express a sensitivity to themes relevant to African Americans. There is no African American way to order a grilled cheese sandwich, but there is an African American way to discuss racial discrimination or white privilege, because it carries with it an energy and a perspective. A single phone call may offer multiple indicators of an African American presence: tone, rhythm, enunciation and metaphorical use.

ORALITY

The Harlem Renaissance writers were able to take elements of traditional African culture and apply them to modern African American culture through the legitimation of folklore and oral histories to written literature. An oral tradition achieves not only contact with the past but also is flexible in dealing with changing present and future.

Orality tends to be:

• Immediate and direct.

• Speaker and audience are one

• It is common and everyday, not isolated and elevated

• It is spontaneous and not rehearsed.

• It is improvised for the purpose and situation.

• It allows individuality to flourish in a group context.

Traditional rhetoric positions rationality and logic at the center.

African rhetoric positions ethics, critical thinking and personal logic at its core.

Traditional rhetoric tends to be direct and explicit.

African rhetoric sees this as crude and unimaginative. The African tradition talks around something in an exploratory way, and allows the audience to make its own decision instead of following orders that are justified logically. When discourse in daily life is too direct it creates problems in relationships. The more indirect methods allow people to structure the ideas in ways they wish and allow for consideration without an open confrontation.

African Americans are more likely to use language as a form of play. Of course, there is always a relationship between what is “play” and what is “real,” and that relationship allows the exploration of issues in a more indirect way as mentioned before. Play is entertainment, but it is also a symbolic exchange of each other.

Signifying is an example. There is an element of indirection, but the apparent significance of the statement may be different from the real significance. Shared knowledge helps the listener interpret the message properly. We call it “reading between the lines,” bur in African American rhetoric it is all important and almost ever-present. We do this through shared knowledge, and shared knowledge is cultural knowledge. Shared knowledge in the African American culture consists of those patterns of communication, behaviors, worldviews and philosophy as understood by the members of that community.

We often say that meaning is in people not in words. Yet, in an oral culture the meaning is often found in the cultural setting than in strictly an individual. Meanings may be ultimately in people, but in the oral tradition meanings are tempered by the text, the context and the pretext.

CONCLUSION

These concepts have been expressed through African American rhetoric, where the elements of African rhetorical theory can be seen. Frederick Douglass, said:

Great is the miracle of human speech – by it nations are enlightened and reformed; by it the cause of justice and liberty is defended; by it evils are exposed, ignorance dispelled, the path to duty made plain, and by it those who live today, are put into the possession of wisdom of ages gone by.

I thought you might want to see what I was doing today.

Best wishes,

Tuna

--

Alfred C. Snider aka Tuna

Edwin Lawrence Professor of Forensics

University of Vermont

Huber House, 475 Main Street, UVM, Burlington, VT 05405 USA

Lawrence Debate Union http://debate.uvm.edu/debateblog/LDU/

Global Debate Blog http://globaldebateblog.blogspot.com

Debate Central http://debate.uvm.edu

802-656-0097 office telephone

802-656-4275 office fax

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=00ae2663-b45b-4db6-a1f9-64408a3339bb)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=624b58a7-d118-47d1-9063-7d17fb1452a5)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=cc2f286c-cf5f-4e64-90fe-ad389650b304)